Newsroom

Early developmental stages of most organisms, such as embryos or floral buds, are highly sensitive to environmental factors. This sensitivity makes the protection of vulnerable offspring and its evolutionary implications a central theme in life history studies. A typical example of this is the amniotic fluid in mammals, which creates a stable microenvironment throughout gestation.

Although primarily aqueous, this evolutionary innovation represents a crucial adaptation in vertebrate development. Similarly, water plays various roles in plant floral development and pollination, such as facilitating flower expansion and regulating temperature through transpiration.

While most species depend on tissue-embedded water (with rare exceptions forming rain-collecting cup- or bowl-shaped structures), no terrestrial plants had been documented to completely submerge floral buds in self-secreted liquid for protection until now.

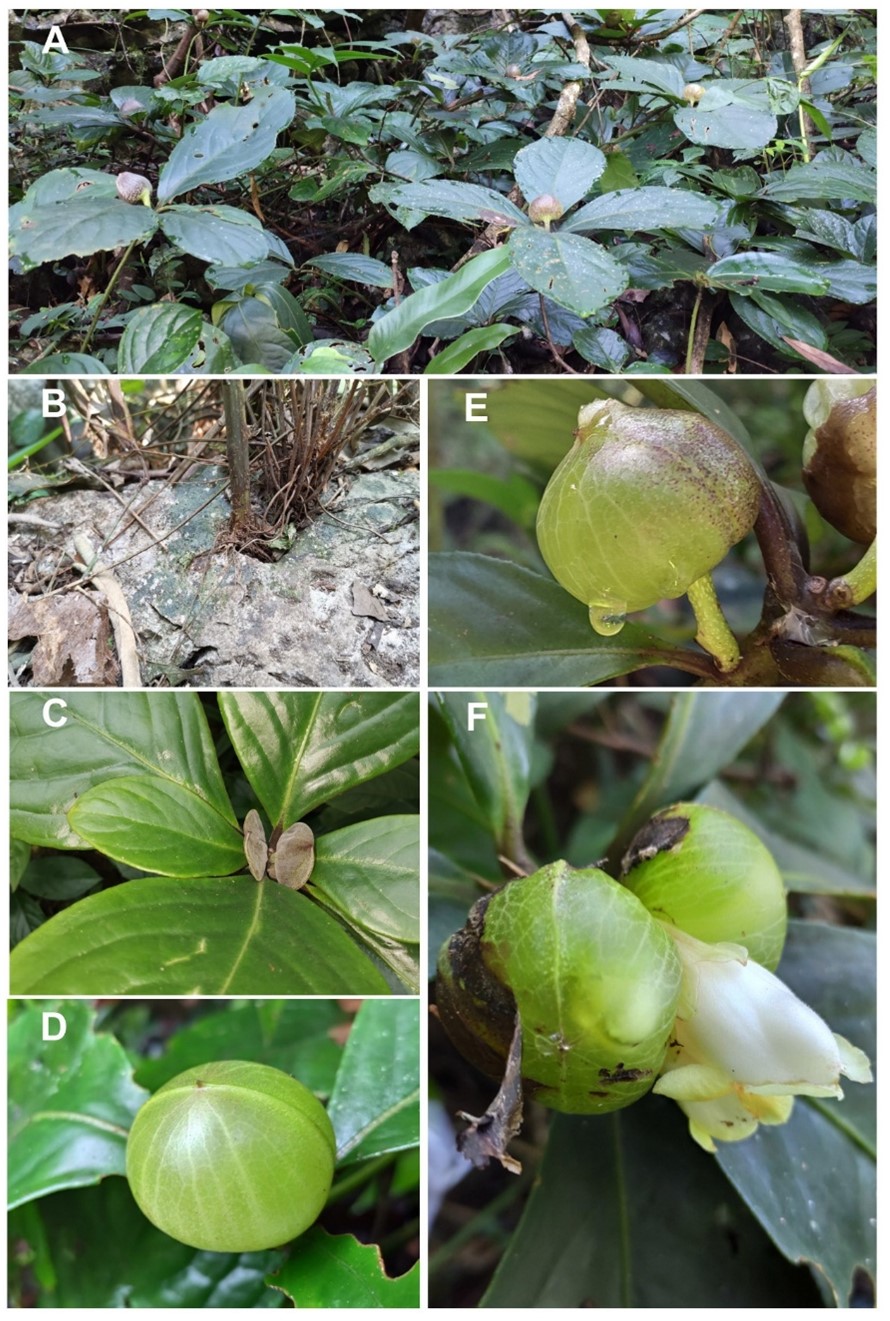

Researchers from the Kunming Institute of Botany (KIB) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, have revealed an adaptation in Hemiboea magnibracteata (Gesneriaceae), a perennial herb endemic to the karst limestone habitats of Northwestern Guangxi and Southern Guizhou provinces in Southwestern China. This work was published in National Science Review.

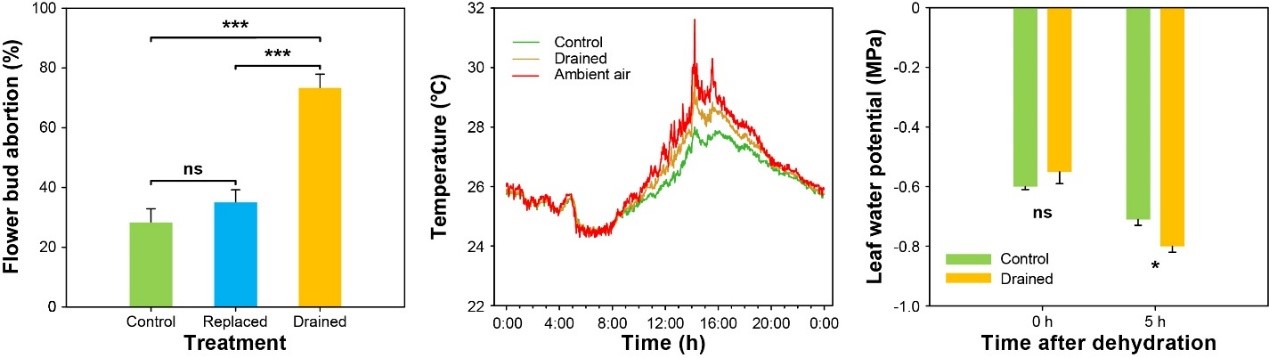

During the early flowering stage, the plant's two opposite bracts form fluid-filled globular or oval chambers that contain up to 20 mL of stem-secreted liquid, fully submerging the developing buds. When the fluid was experimentally removed, the rate of floral abortion significantly increased.

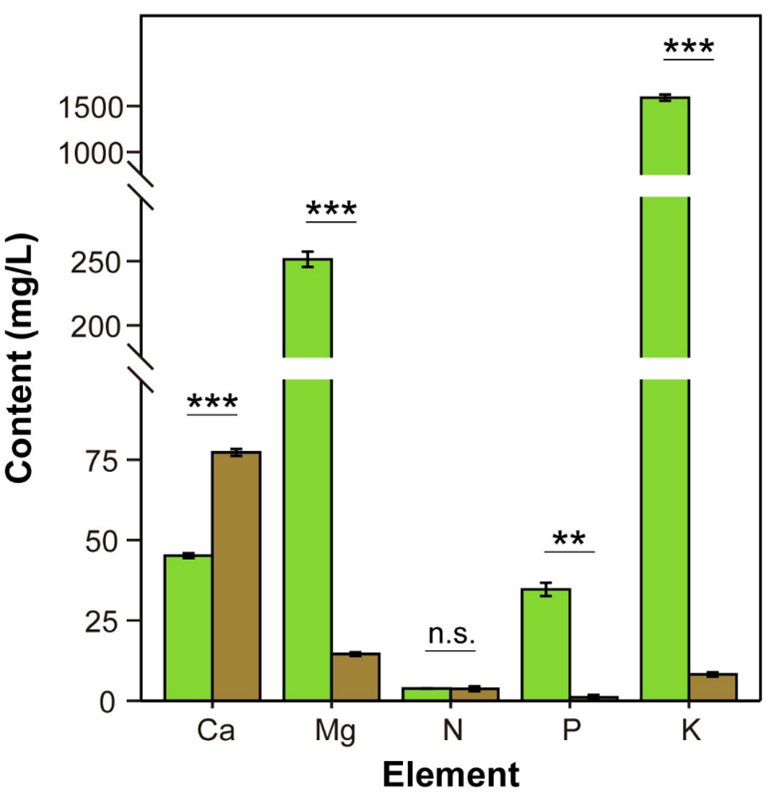

These fluid-filled structures function through three key mechanisms: First, thermal buffering decreases bud temperatures by up to 3.6°C compared to ambient air temperature, which is crucial for mitigating heat stress in karst microclimates. Second, they act as a calcium reservoir, containing 77.3±1.1 mg/L of calcium—1.7 times the concentration found in leaves—helping to counteract calcium levels in high-Ca²⁺ substrates. Third, they enhance drought resilience by facilitating hydraulic redistribution to adjacent leaves during periods of extreme aridity.

Phylogenetic analyses indicate that womb-like bract structure evolves multiple times independently within Gesneriaceae in China.

The discovery provides novel insights into plant adaptations to karst environments and the evolution of multifunctional floral bracts.

Habitat (A, B) and floral bracts (C-F) of Hemiboea magnibracteata. (Image by KIB)

Effects of fluid in womb-like bracts on flower development, flower temperature and leaf water potential. (Image by KIB)

Contents (mean ± SE) of various elements in the fluid from leaves (green) and bracts (brown) of Hemiboea magnibracteata. *** and ** indicate significant difference at P < 0.001 and 0.01, respectively. (Image by KIB)