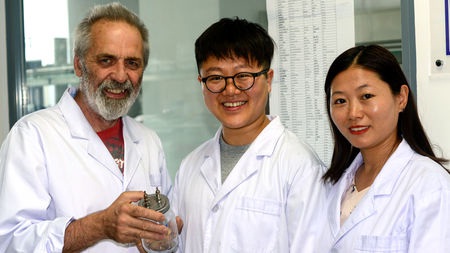

Scottish physiologist John Speakman (left) runs a laboratory in Beijing while maintaining his affiliation with the United Kingdom’s University of Aberdeen, where he also has a laboratory. (Image by AGATA RUDOLF)

China’s evolution into a scientific superpower has altered the politics behind the global movement of scientific talent. Once seen as a benign step in fostering international collaboration, such migrations are now viewed as a potential threat to domestic research by officials in the United States and Australia.

Recently, ScienceInsider examines the nature of interactions between European and Chinese scientists. They focused on how European funding agencies view the issue. And they explored the experiences of several European researchers who have worked in China, including John Speakman, a Principal Investigator at the Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Supporting top talent

The foreign faculty members that ScienceInsider interviewed have enjoyed generous support to set up their labs and fund their research, as well as housing and travel allowances that supplemented their salaries. They usually got a competitive startup package. In addition to what their institutions provided directly, most scientists also benefited from a mélange of initiatives, often referred to collectively as the Thousand Talents Program, that the Chinese government launched more than 10 years ago to attract the world’s best researchers.

The terms of those foreign talent programs vary according to the level of scientific achievement and the sponsoring organization. Spaniard Jose Pastor-Pareja, a fruit fly geneticist working in Tsinghua University, rejects the idea the Thousand Talents Program is a tool for academic espionage. It’s no different than talent recruitment programs in Europe, he says, and equally innocuous.

"When you apply for a faculty position here [at Tsinghua] they encourage you to also apply to Thousand Talents," he says. "It’s totally equivalent to the Marie Curie fellowships under Horizon 2020 for scientists wishing to move back to Europe."

"So it’s ridiculous to see it labeled as a quasi-terrorist organization designed to steal things,” Pastor-Pareja continues. “It’s just another way to recruit talent.”

John Speakman, a Scottish physiologist who runs the molecular energetics lab at the CAS Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology in Beijing, shares Pastor-Pareja’s fond feelings toward the program. “It happened at 10:30 a.m. on 11 July 2011,” Speakman says, recalling the exact time he received an email notifying him that his application to the program had been accepted. That notice, he adds, marked “the start of an amazing adventure.”

Then-director of the Institute of Biological and Environmental Sciences at the University of Aberdeen in the United Kingdom, Speakman had been visiting China four times a year for 3 to 4 weeks at a time, doing fieldwork on the Tibetan Plateau with colleagues from the CAS Institute of Zoology. The award meant he could reverse that arrangement, that is, spend 9 months a year in China and the balance of his time back at Aberdeen, where he continues to run a lab.

Speakman had also wanted to shift his research away from zoology and into lab-based molecular biology. Accordingly, the award allowed him to set up shop at CAS’s genetics institute, which was next door to the zoology institute.

Although he says CAS officials strongly supported his application, Speakman suspects his arrival wasn’t that big of a deal for them. “They probably figured I would stay for a couple of years, and they could say they had a Thousand Talents fellow working for them,” he speculates. However, Speakman’s work on how organisms expend energy was going so well that, when the 5-year award ended, he had no desire to shutter his CAS lab.

"When I came, I was told that the Thousand Talents award was renewable and that I could reapply,” he recalls. “That turned out not to be the case. So the immediate issue for CAS was who would pick up my salary.”

CAS officials suggested he apply to a CAS program, called the President’s International Fellowship Initiative (PIFI), that would pay for 60% of his salary. Getting that 3-year award in late 2017 also solved another problem Speakman was facing.

"I’m 60, and the retirement age here is 60,” he says. “But there are exceptions. And having this grant gives me the right to stay around. My intention is to stay here until I retire.”

Learning the ropes

Western scientists working in China must navigate the country’s formidable—and opaque—research bureaucracy without knowing the rules of the game and without the language skills to learn them on their own. That means relying on the advice and good will of their Chinese colleagues.

One difference between China and many academic labs in the West is the reduced dependence on postdocs. Top Chinese graduate students interested in an academic career are encouraged to go abroad for their postdoctoral training, with the understanding that the foreign experience will put them on the fast track for a position back home. But the downside of that practice is a smaller domestic pool of top-notch postdocs.

In comparison, graduate students are plentiful, as the number of Chinese graduate programs in the sciences is growing rapidly. But the government regulates where they can study. Each institute or university is given a quota, allowing officials to control the influx of students from rural areas into already congested cities.

That quota system can be a challenge for someone setting up a lab at an institution seeking to raise its research profile through new hires. “If an institute grows and takes on more PIs [principal investigators], and the quota isn’t raised, then you end up with a squeeze on the number of students you can supervise,” Speakman explains.

Speakman considers himself lucky. “I was given a pretty favorable deal: I could take in two students one year, and one student the next. Normally, a faculty member would get one student every other year.”

Speakman adds: “Of course, you need contacts. And it can take time for a foreign scientist to develop those contacts.”

Friends and family

Western scientists say there’s no way to avoid feeling isolated after arriving in China. But there are ways to break through that isolation, they say. For some, it’s bringing along their spouse and family. For others, it’s building a new network of colleagues and friends, or embracing the sights and sounds of their new home.

"To really make it work,” Speakman says, “you need to have your family with you. I’ve known people who come by themselves for the 3-month [Thousand Talents–like] program, and that tends not to work out so well. Committing to a big block of time lets you push things forward.”

Speakman says he was fortunate to have a wife willing to relocate and children whose schooling was not adversely affected by the move. (Science)